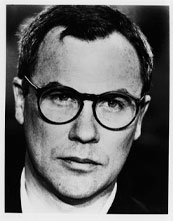

Robert Wilson: the CIVIL warS and After

[The following interiview was originally printed in Theater, Summer/Fall 1985, volume 16: Issue 3, page 72.]Nearly a century before Robert Wilson set to work on the CIVIL warS, his twelve-hour, multi-national megaopera for the 1984 Olympics, another American dreamer, Steele Mackaye, envisioned a stupendous theatrical pageant to astonish the public. Like the CIVIL warS, Mackaye’s epic “spectatorio” on the life of Columbus, The World Finder, was intended to commemorate a great public event, the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, on the grandest scale imaginable. A palatial, ten-thousand seat auditorium was to be specially constructed near the shore of Lake Michigan with an immense domed cyclorama and twenty-five stages which were to move across a vast expanse of water on six miles of submerged railroad tracks. The production also promised a chorus of six hundred voices which would surround the spectator from all sides, a massive symphonic score by Antonin Dvorak (later to become the New World Symphony), a curtain of incandescent light, full-scale sailing ships and a multitude of newly patented devices to produce such natural wonders as sunsets, storms, waves, stars and rainbows. But like the CIVIL warS, Mackaye’s great theatrical vision ended in financial collapse, and not in transcendent glory. It took an economic calamity of national consequence, the Great Panic of 1893, to bring down The World Finder, while Wilson’s extraordinary venture fell victim to a far less momentous, if for him no less devastating malaise, American indifference.

When Theater last spoke with Robert Wilson, nearly two years ago, he was looking ahead to the creation of his most ambitious work with anticipation and optimism; now he discusses the unhappy circumstances surrounding its collapse and its effect on him as well as the numerous projects that have come to occupy him in the past year.

The journey is a central motif in the plays and operas of Robert Wilson — we travel with humanity through time and history, through inner and outer space, no journeys toward both universal understanding and apocalypse — and these days Wilson seems to be journeying through time and space almost as freely and incongruously as the beings who occupy this theatrical universe. One day finds him in Barcelona, the next Holland, a week later Texas, then Munich or Rome. Every destination is a stopover as he moves restlessly through the world pursuing new challenges, new commissions and celebrity itself. Wilson’s art offers a striking contrast to his own life; one moves with the cool, effortless calm of a cloud drifting across the sky or a pine tree blowing gently in the breeze (to cite two of his favorite comparisons), the other barrels forward like a runaway express train, creating confusion as it passes and sending harried co-workers scurrying for cover. The art opens onto a vista of buoyant dream images, the life is a kind of administrative nightmare. Both are his creations.

At the present time Wilson’s eighteen-hour workdays are filled with conferences, interviews, fundraisers, the prospect of missed deadlines and, more than anything, his own relentless energy. While he complains of overwork and exhaustion, these complaints are nothing compared with those that would be heard if he were ever to find an empty day on his calendar. Some friends and associates have noted the potential hazards, both physical and artistic, of such a crazed, obsessive existence, but Wilson gives no indication of pulling back or slowing down.

Unlike Steele Mackaye, who never really recovered from the collapse of his dream, Wilson seems to have rebounded from the CIVIL warS with renewed vigor and redoubled activity. The future promises a multitude of bold plans, new works and further — if as yet barely imagined — journeys.

In late March of 1984, less than three months before its scheduled premiere in Los Angeles, Robert Fitzpatrick, Director of the Olympic Arts Festival, announced the cancellation of the CIVIL warS due to lack of funds. Although it must still be a painful subject, could you tell us more about the last days of CIVIL warS and your eleventh hour efforts to salvage the project?

What happened was Fitzpatrick and I agreed the final deadline would be April 1 and that we would issue a joint statement if it wasn’t going to happen. I was in Rome preparing the Italian section of CIVIL warS the week before the deadline and I realized that it was going to be next to impossible to find the money for presentation. So I decided to call Volker Canaris, the Intendant of the Cologne Schauspielhaus, who had been very supportive and ask him if there was any possibility of doing one of two things. Could we present the entire work there? — possibly some time in the future, though this would be very complicated wince all the monies had been given for the Olympics in Los Angeles. But then I was also beginning to realize that we could take the European sections of the CIVIL warS, present them somewhere in German or France and transfer them via satellite to Los Angeles. Then the Knee Plays, which were about to be staged in Minneapolis, could be moved to Los Angeles and seen live. Since we no longer needed such a big auditorium, we could have moved to a smaller theater which would have further reduced costs. The Japanese section was built and ready for presentation and we could have either pre-recorded it or transmitted it live from a theater in Tokyo. We could have even had simultaneous satellite presentations in Rome, Rotterdam, Marseilles, Nice, Lyon and perhaps other cities in France so that all the theaters in the various host countries that had sponsored the project would have a chance to see the complete work.