Robert Wilson: the CIVIL warS and After

While the Charpentier opera was performed as written, you did throw out the original prologue and replace it with a scene from the CIVIL warS (II, a), a rather cunning way of getting another section of that work staged and paid for — and something not many others could have gotten away with.

The prologues of baroque operas were allegories which didn’t necessarily have anything to do with the rest of the opera. Once I knew that I started thinking.

Did this unorthodox substitution bring cries of outrage?

Oh, yes. They booed me every night. You’ve never heard such booing.

While you’ve pointed out how dissimilar the two stagings were, each Medea did share in a body of common images, something that was particularly apparent in the closing tableaux of each production.

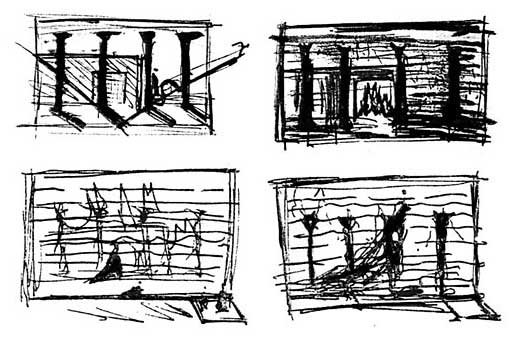

I’ll show you. The opera I did with Gavin is really just like Euripides. I have Medea descending on a diagonal line in her serpent chariot and then flying off on another diagonal rising off of it. Two acts earlier I had a group of weavers anticipate this scene by tracing the line of her ascent with a gold thread. For the final scene I have the house again, only now the entryway is engulfed in fire. The four pillars have turned into these huge cat gods and a projected image of water fills the sky. Jason walks into a fiery entryway and his robe falls off, revealing a huge serpent wrapped around his body. Finally, the big stone cats move downstage and silently face the audience. For the last scene of the Charpentier opera I had a house on gauze and Jason kneeling at the front stage. Cindy is with Didi on the platform plucking a dead bird. Then you see fire and water, only here it’s a painting and not a projection. Then, Medea begins rising upward and as she rises, the house disappears and I reveal the same stone cats you saw in Euripides. Jason slowly falls over backwards and Medea rises higher and higher through the fire and water as though she were flying away.

You’re also planning to stage King Lear in Hamburg in 1987, with Heiner Müller doing the translation. Let me start with the obvious question: why Lear?

I like it. I’ve been thinking about it a long time.

I’ve been told that you actually created a short piece based on Lear when you were preparing KA MOUNTAIN at Royaumont Abbey back on 1972.

That’s right. In fact, I started reading it at that time. There was a gardener at Royaumont who had a very dry wit and I thought he might be right for Lear — at that time I was mostly working with non-actors. I did something with him that might have included a little of the text, I can’t remember. I also did a speech about Lear in KA MOUNTAIN. I balanced a piece of paper in the palm of my hand for Cordelia.4

In both Sigmund Freud (1969) and The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin (1973), two works dating from this period, you envisioned your protagonists as human beings whose lives had been broken by a terrible loss, the death of a grandson in one case and a beloved first wife in the other. Lear suffers the same fate at the end of the play and it also proves a loss beyond endurance. Was this theme what attracted you to the play?

I hadn’t thought about that but it is a recurring theme in my work. I just did a death of Lear for the epilogue of the Cologne CIVIL warS. I had him crossing the stage with a crumbled newspaper in his hands for Cordelia. “Howl, Howl, Howl.” It was played by Peter-Pilz, an actor in his late seventies who had been a member of the Berliner Ensemble and appeared in a lot of Brecht’s original productions. He was retiring from the theater and this was his last show. I wanted him for my Lear in Hamburg but he said no, he was too old. We went to see a terrible production of King Lear together and when it was over I asked him what he thought but he didn’t say anything. Instead he told me a fantastic story.

4““The great tyrant’s more than eighty years of age, stumbles on the stage, and carries within his arms his beloved Cord-dark-Cordelia, in all of the unwanted places in the wasteland, that roll into darkness, and in the sun, out of the dark . . .” Quote by Ossia Trilling in “Robert Wilson’s KA MOUNTAIN,” The Drama Review, June 1973.

In May of 1973, Wilson also presented a single performance of a work entitled King Lyre and Lady in the Wasteland at his New York loft. While he says the piece was not based on Shakespeare’s play, he believes he made “some kind of reference” to the text.