Robert Wilson: the CIVIL warS and After

Why do you think the collaboration has been so mutually satisfying?

I don’t know, maybe it’s because I’m from Texas and Heiner is from East Germany and our backgrounds are so different and . . . somehow it works.

This fall you staged two versions of the Medea legend at the Lyon Opera, a modern opera with music by Gavin Bryars based on the text of Euripedes and the first revival in nearly three hundred years of Marc-Antonie Charpentier’s Medee3.

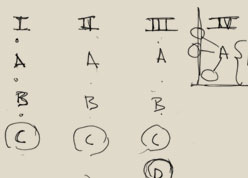

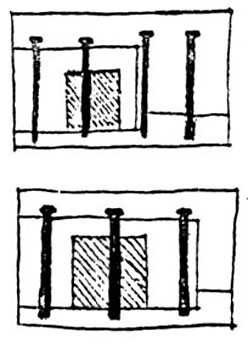

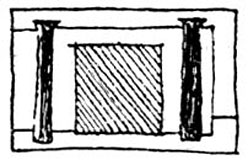

They were both so different. Euripides’ Medea is a very modern story. Like something you might read in the newspaper. The Charpentier opera is a baroque work having more to do with Christian concepts of love and guilt. The ancient text is much more contemporary. I’ll probably tell this story wrong but I’ve heard that someone once told Callas that her Medea didn’t seem very Greek and she said, “Oh, Medea’s not from Greece, she’s from Brooklyn.” And it’s true, she’s a very modern woman. The two productions were entirely different. For the Euripides I created a real house and sky, and a series of columns — one fewer in each act, as though a camera was slowly zooming in on the scene. Like this.

The design was classical and very realistic while the décor for the baroque Medea was very abstract. Just a bare stage and a series of drops painted like my own graphite drawings. The way the performers moved in the two pieces was different too. The staging of the Euripides was based on geometric patterns with the actors’ bodies very centered with the Charpentier tended to be circular with flowing movements, an asymmetrical body line and sweeping baroque gestures. In the Euripides I had Medea standing downstage like a column through most of the piece. It’s as if she’s been standing there forever. No one ever touches her, no one ever gets near her. The only time she moves is when she goes to the children. In the Charpentier, she’s moving all the time. It’s in the music.

In Prologue to Deafman Glance, an early work you continue to revive and restage, we see a tall, impassive woman in a black dress silently murder her two children without explanation or emotion. Would we be right in assuming that your Medea grew out of this piece?

Yes, there’s a connection. I didn’t think of Euripides at that time but after I made the piece, I began to realize that it was a kind of Medea. It was like the seed of my Medea, like the bud of a flower.

There’s a preoccupation with murder in all your works.

But I don’t see murder literally. I see it as something that can take place in the glance of an eye or in a mother reaching for her baby. You know, Euripides never shows the murders. They’re only discussed. So I decided that’s what we’d do. I had everyone sitting at a table in contemporary clothes discussing the text. During rehearsals various members of the company brought in material that they thought related to Medea, like newspaper articles on domestic murders or child abuse, and we sat at a table and read through them, which is also how we began studying the text at the first workshop. Later, I thought that this is how we should do the murder scene, so I took bits and pieces of their texts and made a structure of them. Since this was the climax of Medea, I treated the scene in a very different manner. Instead of the rich and sensitive lighting I used in the rest of the opera, I made the light in this scene harsh and flat. It was such a shock. By cutting away all the theatrical effects, the scene became the most theatrical in the production. The murder isn’t seen in the Charpentier either. What I had was two performers (Cindy Lubar and the French actress Evelyne Didi) on a white platform downstage — like the one I had for the kneeplays in Einstein — who played cards or knit or read or peeled vegetables in the same way that a baroque audience talked or ate or did other things while watching a performance. Near the end of the first act, they left the platform and a black-hooded mystery man appeared and went through the motions of stabbing these two people who weren’t there. And it was never clear who the two performers were. Were they the children? Were they the public watching the performance?

The Charpentier opera has a French libretto by Thomas Corneille but for the Euripides Medea you created your own multi-lingual text, much of it in modern Greek.

Medea is the first time I’ve ever dealt with a classical text and I was very faithful to it. I decided on modern Greek because it’s a very beautiful language and sounded better for some things than the ancient text, although I kept the final chorus in the original Greek. I also had some parts in English because the work was originally going to be done here. While the theater in Lyon decided they wanted the English dialogue in French, I still kept Jason’s texts in English because I think of him as an American businessman. Like Peter Ueberroth. I even had him dressed in a business suit.

3 Wilson’s production of Médée (1693), an opera in five acts by Marc-Antoine Charpentier, received its first performance at the Opéra de Lyon on October 22, 1984. The American soprano Esther Hinds (replacing the originally scheduled Jessye Norman) appeared as Médée and Michel Corboz conducted. The Wilson-Bryars Medea was first performed in Lyon on October 23, and later appeared at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris under the auspices of the Théâtre National de l’Opéra and the Festival d’Automne. The opera was preceded by a prologue which featured the Medea texts of Heiner Müller (Despoiled Shore/Medeamaterial/Landscape with Argonauts). Yvonne Kenny appeared as Medea and Richard Bernas conducted.